Book three 1800-1900. Chapter two: The Church and her officers

After the death of Robert Welton, Charles Bourchier was instituted as vicar of Sandridge. He was a native of the place, having been born at Sandridge Lodge in Marshalswick Park; he had as his godparents a Duchess, an Earl and a Baronet. To this young man was committed the care of the people of Sandridge for forty-nine years. In his first year as vicar he baptised two infants, and that was about all he ever did in the village. The best that can be said for him is that he provided Sandridge with a succession of hardworking curates who took their duties seriously. These poor men had to live in a house with an open cesspit under one of the rooms.1 One of these curates was Thomas Henry Winbolt, who came to Sandridge in 1847. His work for the school and for the safety of the village has been mentioned. During his twenty-five years in the parish he prepared and presented 250 people for confirmation. Shortly before his departure he was specially commended by the Chief Constable of Hertfordshire, who said that it was chiefly due to his work that Sandridge was almost free from detected crime.

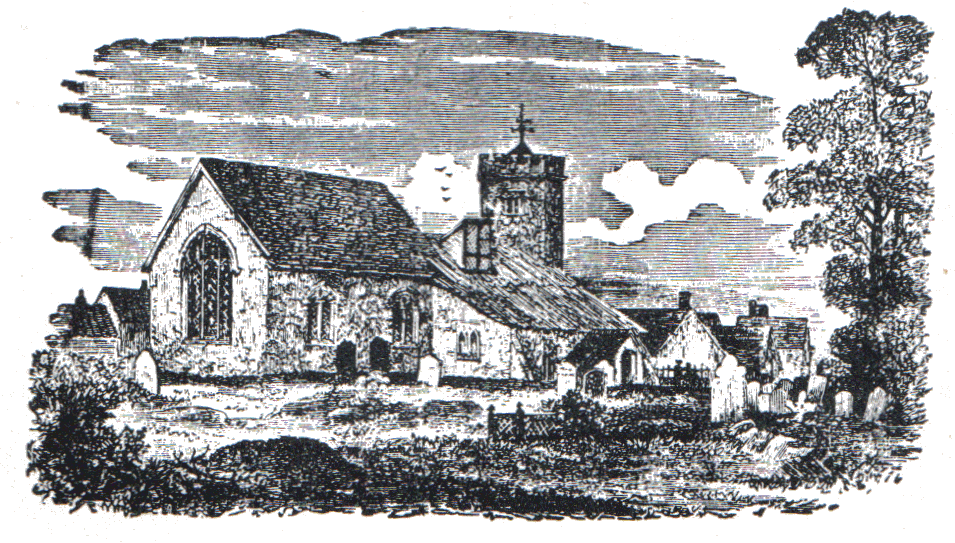

It was during the curacy of William Ryland that it was decided to replace the church tower which had fallen down in 1693. The parish officers, with others supporting them, decided in 1836 that a new tower should be built. Unfortunately, they tried to save money by dispensing with the services of an architect and by employing only an incompetent builder, Mr. Hall of Hatfield, who undertook to do the job for the low figure of £80 to £100. The church was normally maintained by a rate of 3d. in the pound, but this was doubled, and then the next year trebled, in order to pay for the bells and tower. The builder began his operations, but a few months later complained that he underestimated the cost and could not complete the tower for as little as £100. The vestry meeting showed no sympathy; by December 1837 the tower was completed; Mr. Hall continually complained about the cost and he finally obtained an extra £40, without the vestry admitting liability. That same year, when William IV died, the two cracked bells were sent to Whitechapel to be recast. The church looked as shown in the illustration for the next fifty years. (The clock was inserted in 1847, a gift of Mr. Thomas Powney Marten of the East India Company.) The two bells came back and were hung in the new tower and rung in time for the coronation of Queen Victoria; the larger of the bells is still in use. Three years went by and then one Sunday morning during service, there was an ominous noise and a gap appeared in the nave roof. The tower had taken a slight lean to the west, and it was discovered that whereas the east wall was on old foundations, the west wall of the lower had been built on graves, which had subsided. After eighteen months delay a London surveyor inspected the tower for a fee of nearly £9 and advised that it be shored up for the winter, which was done by William Paul. The churchwardens demanded of Mr. Hall what he meant to do about this deplorable stale of affairs. After another inspection by a surveyor, who stated that the tower needed underpinning, Mr. Hall was obliged to make good his inefficient work and it is recorded that on Lady Day 1844

the works necessary for the security of the tower of the parish church have been satisfactorily completed by Mr.Hall, and the tower now appears in all respects satisfactory".2

The erection remained until 1886, and there are still a few parishioners who remember it.

William Archer, aged thirty, was in 1836 appointed verger. Besides ringing the two bells he was expected to keep order in church, keep the churchyard tidy and report damage. All this was for a shilling a week. His boots were rather noisy, so the wardens obtained for him a pair of slippers for two shillings, which lasted for fourteen years. Keeping order in church was not always easy and Archer had trouble with one of the notorious Paul children. Matthew William, at the age of seventeen, heaved a stone at the poor verger in the churchyard, and although the stone missed its mark, he was duly fined. This lad probably inherited his high spirits from his grandfather, who got into trouble for his behaviour at a Vestry meeting. He was told that his charges were extravagant; when he gave the meeting his considered opinion of them. The nine farmers present agreed that he

be not in future employed upon any parish business.

Instead, they employed his son. Mr. Archer also dug the graves and his tombstone contains the following lines:

For many years I added dust to dust,

Ashes to ashes in my neighbours' graves,

Now Lord, my dust and ashes I entrust

To Thee, whose death from death eternal saves".

For forty-nine years Sandridge had been without a resident vicar and Dr. Griffith was therefore given a good welcome in 1872. Of a nonconformist family and educated at Cambridge, he brought to Sandridge his Puritan views. He had many children of his own and he expected them to renounce the devil and all his works, which included in his view dancing and sports. He was one of the most notable vicars Sandridge ever had, and he was known as Doctor Griffith, having become a Doctor of Law some years previously. In that period the clergy were still of the gentry and were expected to live as such. That is why the enormous old vicarage was built at that date. Six and a half acres were bought for garden and meadow, the price being £400; £200 came from the Duchess of Marlborough as long ago as 1729, and the remaining sum was a grant from Queen Anne's Bounty. A few months after the new vicar's appointment the villagers cleaned the church and cleared away many years' accumulation of dust and dirt. Oil lamps were hung, replacing a few candles on the backs of the box pews, which had shed a dim light on winter afternoons.

Dr. Griffith's most outstanding work for Sandridge was the restoration and enlargement of the church. When he came he found the church in an almost ruinous slate and he quickly decided to rectify the matter and make the church secure for posterity. He would not, however, start work until all the necessary money had been subscribed; This great task took fifteen years. Many gave generously to the fund according to their means: £434 came from the Martens of Marshalswick, who had certain of the old box pews reserved for their use, but the continuance of this privilege was thwarted by the acceptance of a grant of £60 from the Church Building Society, which was given on condition that all seating was free and unrestricted.

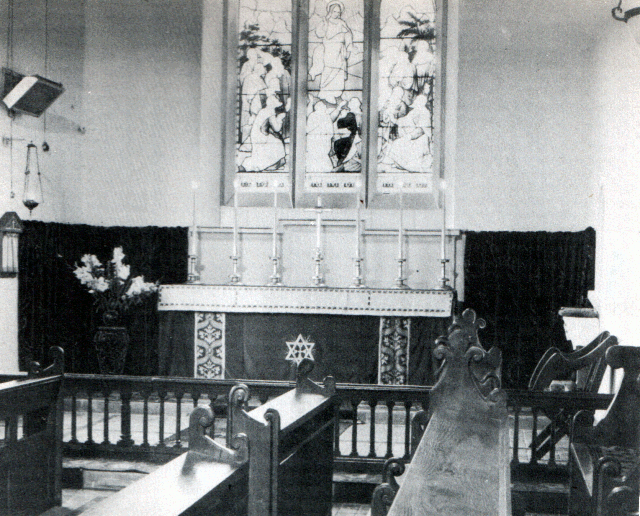

The work was carried out by Messrs. Gregory and Company, under the direction of two architects at a cost of £3,808. Building operations look over a year, during which time a new tower was built, a new root for the nave provided and the whole fabric was repaired and made secure. The whole or the west end or the church dates from this time, and all the nave above the Norman arches, including the six clerestory windows, likewise the pews, choir stalls, pulpit and lectern, and the wooden floor blocks. The mediaeval tiles which were round here and there under the pews were re-laid in the sanctuary. The curious wooden structure above the ancient stone screen was also erected at that time, replacing the solid wall of the original builders. The idea was to allow sound to move more easily between chancel and nave. The organ was moved from the chancel to the west end where it remained until 1914. The restorers were careful to preserve the old Scratch Dial on the exterior or the chancel. The vicar expressed the hope that

the work done will last good, needing only ordinary repairs, for another eight hundred years.

During the restoration of the church public worship was carried on in the village hall which the vicar had built in memory or his eldest son. He also did much to improve the housing conditions in the village and to increase the amount of land available for allotments, which are still such an important feature in village life. Of Dr. Griffiths spiritual work his obituary stated:

Every house in the village soon knew him personally and there were few where he was not welcomed.

He hated shams; like Chaucers poor parson he was learned, and yet simply practical. and spared no pains to make his weekly teaching as complete and true as he could. All the same this teaching seems to have been definitely one-sided, and the next vicar, James Cruikshank, had a difficult task in restoring the balance. He came to Sandridge without any previous parochial experience but he made up for it by hard work and sincerity. In the Sandridge Magazine, which he founded we often find him deploring the paganism of the village. He left in 1899 and the vicars since his day have continued to alternate between the Evangelical and Catholic outlooks. Since the Church of England is both Catholic and Evangelical this may be a good thing, even though it creates difficulties. Although Austin Oliver spent too much time hunting foxes, for he found his promise to Lord Spencer not to hunt six days a week difficult to keep, and although a perfect example of the old gentry vicar, his humanity glows in his Recollections of Sandridge and his comment that he thought

the farmers or Sandridge the best churchmen and finest sportsmen in the world

provides a moving tribute. Hugh Anson, the last or the gentry vicars, who was at Sandridge throughout the Kaiser's war, did valuable work, the results of which are still apparent. Edward Giles will long be remembered for his work. and not least for his scholarship and labour in preparing a permanent record or time gone-by in his parish.

|

Sandridge, Hertfordshire, England |

|---|---|

| About | Main article |

| Places | Location · Parish bounds · St Leonards church · Nomansland · Sandridgebury · Marshalswick · Fairfolds · Harefield · Waterend |

| People | Rober Thrale (the elder) · Thrales of Sandridge · Richard William Thrale · Thomas Thrale's 1600 will · Johnathan Parsons' 1768 will · Ralph Thrale's goblet |

| Genealogy | Sandridge vital records · 21 people called Ralph Thrale |

| More | Thrale.com Sandridge forum · Historic Sandridge · Historic Sandridge Revisited · Village website · Parish Council |